Capital Gay, 30th September 1983

Monthly Archives: April 2013

Islington takes the wraps off pledges (5.8.83)

How Margaret Hodge’s policies allowed paedophiles to infiltrate Islington children’s homes

Margaret Hodge became leader of Islington in 1982 and stayed in the job until 1992 when it became apparent, due to exposure by whistleblowers working with the Evening Standard, that every one of Islington’s eleven children’s homes was staffed by members of a paedophile network who were sexually abusing children in care, and were involved in prostitution, child trafficking, and the trade in images of child abuse.

In a recent Guardian interview, Margaret Hodge attempted to talk her way out of responsibility for the child abuse scandal at Islington Council: All that happened when we didn’t really understand child abuse in the way that we understand it now. This was the early 90s … It was only beginning to emerge that paedophiles were working with children, in children’s homes and elsewhere, and so I think my great regret there was believing without question the advice that I was given by the social services managers.

This isn’t what really happened. Hodge was told about a paedophile network operating in Islington’s children’s homes, but she refused to listen.

Margaret Hodge is also silent about how her policies directly enabled paedophiles to work with children and escape detection. Islington Council’s Equal Opportunities policy was unveiled in August 1983.

It promised “positive action” to recruit gay staff, gave an assurance that all council jobs would be open to gay applicants – including the sensitive area of work with children, promised that nobody would be put at a disadvantage if they came out as gay at work, and pledged ‘adequate redress’ to any lesbian or gay man who was subjected to “any harassment, whether physical or verbal” by members of the public or fellow workers…

…Job advertisements will in future carry an announcement that Islington Council does not discriminate against lesbians and gay men, and will invite them to apply.

Labour councillor Bob Crossman was the only person to speak in the “debate” on the proposals, after the policy had been proposed formally by Council Leader Margaret Hodge.

On the face of it, this was an honourable policy, setting out to give protection to an oppressed minority. And why shouldn’t gays be able to work with children, surely they weren’t they any more likely to abuse children than heterosexuals?

Unfortunately, things weren’t what they seemed. The gay liberation movement had been infiltrated by paedophiles as early as 1975. There were paedophiles posing as gay men and hiding behind the gay rights banner to avoid detection. The largest and most influential organisation in the gay rights movement was the Campaign for Homosexual Equality (CHE). At their national conference in Sheffield in 1975 they voted to give paedophiles a bigger role in the gay rights movement. CHE were affilated to the Paedophile Information Exchange (PIE), who campaigned for the age of consent to be reduced to 4, which would effectively legalise paedophilia. Copies of PIE’s manifesto were sold at CHE conferences.

This association between the gay rights movement and paedophiles carried on for years, and was still going strong in 1983 when Margaret Hodge decided to proactively hire gays (and therefore paedophiles) to work with children at Islington Council. In September 1983, Capital Gay reported that CHE had “stepped up support for the Paedophile Information Exchange”.

It’s hard to believe that Margaret Hodge wasn’t aware that the gay rights movement had been infiltrated by paedophiles, and that many ostensibly ‘gay’ men were in fact paedophiles. Her late husband, Henry Hodge, was chairman of the National Council of Civil Liberties (NCCL) since 1974, and the NCCL were affiliated to the Paedophile Information Exchange. In 1978, the Protection of Children Bill was put before Parliament, and the NCCL’s official response stated that images of child abuse should only be considered ‘indecent’ if it could be proved that the child had suffered harm. The document was signed by the NCCL’s legal officer, Harriet Harman, who along with her husband Jack Dromey (also an NCCL official), were close friends of the Hodges.

The council’s policy also stated that any gay man (and therefore also a paedophile who claimed he was gay) would be protected from harassment. This meant that staff members who made allegations of child abuse against gay (or paedophile) members of staff would be accused of harassment, and any disciplinary action was dropped. This also meant that staff that should have been investigated had ‘clean’ ecords and were allowed to gon on and abuse children at other children’s homes after they left Islington.

From The White Report, 1995: “…it is apparent from this analysis that the London Borough of Islington did not in most cases undertake the standard investigative processes that should have been triggered when they occurred. It is possible, therefore that some staff now not in the employment of Islington could be working in the field of Social Services with a completely clean disciplinary record and yet have serious allegations still not investigated in their history.” The report went on to say that Islington Council was “paralysed by equal opportunity“, and “the policy of positive discrimination in Islington has had serious unintended consequences in allowing some staff to exploit children for their own purposes.”

Islington Council had adopted another policy the previous year which meant that any firms wanting a grant or loan from the council would have to “produce evidence of their commitment not to discriminate against gay staff”. This meant that companies associated with Islington’s children’s homes would also have difficulty reporting paedophiles without being accused of homophobia. This may explain how one of the staffing agencies used by Islington Council had also been infiltrated by paedophiles.

Islington was probably the first council to implement a policy that made it easier for paedophiles to work with children. In September 1983 it looked like Islington were influencing Lambeth Council to implement the same policy. Lambeth also went on to have a paedophile network operating in its children’s homes, over 200 children were believed to have been abused.

Margaret Hodge attempts to talk her way out of Islington paedophile scandal

In yesterday’s Guardian, Margaret Hodge spoke about her time as leader of Islington Council, when it was proved that a paedophile network had been sexually abusing vulnerable children in every one of the council’s children’s homes.

Her own tenure was not without its controversies: within weeks of taking on the job, accusations resurfaced that while she was leader of Islington council, from 1982 to 1992, she had not done enough to follow up allegations that a child abuse ring was operating in her borough. When a victim protested her appointment as minister, she described him as an “extremely disturbed person” and tried to prevent the Today programme from airing his claims; she eventually had to make a formal apology in the high court and pay £10,000 in damages to a charity. “All that happened when we didn’t really understand child abuse in the way that we understand it now. This was the early 90s … It was only beginning to emerge that paedophiles were working with children, in children’s homes and elsewhere, and so I think my great regret there was believing without question the advice that I was given by the social services managers. I can tell you that I sat across the table, like you and I are sitting across the table now, and said, are you telling me the truth? Is that all I need to hear? And in the end, I believed them. I should have challenged that. [That] I really regret. What I didn’t do was hear the voices of those kids who had suffered abuse. I should have.” Full article

It appears that Margaret Hodge is attempting to rewrite history in anticipation of the Islington Children’s Homes scandal resurfacing due to the current Peter Righton investigation. The Peter Righton paedophile network abused children in schools and children’s homes across the UK for decades, and there are already links between the network and Islington.

Margaret Hodge was warned of paedophiles operating in Islington Children’s Homes, yet she did nothing to help the children who were being abused.

For an account of what really happened with Margaret Hodge and Islington Children’s Homes, read this Evening Standard story from 2003:

‘Yes Minister, you were told about child abuse in the care homes, yet you refused to listen’

by David Cohen

IMMEDIATELY after Tony Blair appointed Margaret Hodge as the new Minister for Children in his recent reshuffle, phones started ringing among former social workers who had once worked under her. “It’s like putting the fox in charge of the chickens,” one commented in disgust. “A sick joke,” remarked another.

These social workers couldn’t help recalling the inside story of an appalling child sex abuse scandal many of us have forgotten. In 1990, when Mrs Hodge – then Mr Blair’s neighbour in Richmond Crescent, Islington – was the leader of Islington council, these senior social workers had reported to her that a paedophile ring was operating in the borough and that children were being sexually abused in Islington care homes.

Mrs Hodge’s response was revealing: she chose not to back a thorough investigation. Instead, she dismissed their concerns and accused these social workers of being ” obsessional”.

When the story was exposed in the Evening Standard two-andahalf years later, in October 1992, her re-sponse was equally aggressive. She accused the newspaper of “a sensationalist piece of gutter journalism”. It would be a further two-and-a-half years and five independent reports later before she would half-heartedly admit that she was wrong. Yet she would have known as early as 1991 that paedophiles were preying on children in Islington’s care.

In 1991, Roy Caterer, a sports instructor at a boarding school used by Islington, was arrested and sent to prison for seven-anda-half years for abusing seven boys and two girls, some of them in Islington’s care. Caterer admitted to police that he had abused countless Islington children over many years.

In 1995, an independent report prepared by Ian White, Oxfordshire’s director of social services, utterly vin-dicated the Evening Standard. It lambasted the council and confirmed that the social workers and the Stand-ard, whose reporters went on to win prestigious press awards, were right. It said, in part: “The inquiry has charted an organisation in the late 1980s and early 1990s that was chaotic. Such a chaotic organisation breeds the conditions for dangerous and negligent professional practices in relation to child care.”

Mrs Hodge led Islington council from 1982 to 1992.

What the Standard uncovered – after taping hours of interviews with staff, parents, children and police over a three-month period – was a horrendous dereliction of duty by the council that routinely exposed the most vulnerable children in its care to paedophiles, pimps, prostitutes and pornographers.

What the Standard and the White report found inexcusable was the council’s refusal – led by Margaret Hodge – to listen and act when experienced staff and terrified children tried to articulate what was going on. Their testimonies lifted the lid on horrific events that were taking place in Islington: teenagers selling sex from their council homes, a girl knifed by a sexual abuser inside a children’s unit, a girl and a boy who shared a bed with a known paedophile, a 15-year-old boy fostered with a suspected paedophile – overriding the vociferous protests of social workers – who later sexually abused the boy as predicted. We could go on and on.

The tragedy was that from the moment these children came to live in the seemingly safe children’s homes under the care of Islington council, they became fair game.

Some of the very people who were supposed to protect them were involved in their sexual abuse. On top of all this, the social workers who tried to protect them were pilloried by Margaret Hodge and her social services directors. The damage done to such children is beyond comprehension.

But the story of the Islington child sex abuse scandal would never have seen the light of day had it not been for the brave actions of a single secret whistleblower. Until today, the identity of this whistleblower has remained a secret. Nobody outside a tiny coterie of key players knew who he – or she – was. And so it would have remained. But in the wake of Mrs Hodge’s appointment as Minister for Children, the whistleblower has decided to blow her cover. She doesn’t come to this decision lightly.

But so indignant is she at this ” cynical appointment” that she has decided to tell – for the first time – the full story of what really happened.

She wants us to know the truth about our new Minister for Children. For Mrs Hodge and her management team were never made properly accountable for what happened to the children whom they failed. Instead, the whistleblower and her supporters were marginalised, whereas Mrs Hodge is now a rising star in government.

The whistleblower’s identity, we can reveal, is Liz Davies, 55. She is now a successful senior lecturer in so-cial work at London Metropolitan University.

But back in 1990, Liz Davies was the senior social worker heading up a team of six in the Irene Watson Neighbourhood Office, one of 24 similarly decentralised council offices in Islington. In speaking out, she is joined by another insider who has also hitherto remained silent – her former ally and manager, David Cofie, 63. Other social workers from that time in Islington are prepared to support the position taken by Mrs Davies and Mr Cofie.

“Margaret Hodge definitely knew everything right from the start, and by ‘start’ I mean more than two years before it was exposed in your newspaper,” begins Mrs Davies, talking to the Standard in north London. “She knew as early as April 1990 that we had uncovered serious evidence of sexual abuse among children in our care and yet she chose not to pursue our investigation.”

Her story starts at the beginning of the Nineties. “I noticed that there was a sudden unexpected increase in vulnerable teenagers coming to our office to see social workers,” recalls Mrs Davies. “They’d be crying and depressed and they didn’t want to talk. I didn’t understand it. We spent a lot of time engaging with these children and began to closely investigate their lives.”

Soon Mrs Davies and Mr Cofie began to realise that sexual abuse was part of the picture.

“The children were displaying classic symptoms of sexual abuse and we started to hear disturbing stories of a paedophile ring. At this point, we had no idea as to the scale of the network, or that the children’s homes – under our control – were involved. We began working closely with the Islington Child Protection officers and following local and national child protection procedures to the letter.”

Mr Cofie and Mrs Davies collated the information in a series of reports that were presented to the directors of social services. They responsibly asked for additional funds for two youth workers to be seconded to their team to help with investigations, which were snowballing and threatening to overwhelm them. But their request drew an icy rebuke from their council leader. In a memo to the head of Isington’s social services, John Rea Price (a copy of which is in the possession of the Standard), dated April 1990 – written on “Islington council leader’s office” stationery and from “Margaret Hodge, Leader” – Mrs Hodge wrote the following: “Sexual Abuse in Irene Watson Area: David Cofie raised the issue of sexual abuse among eight- to 16-year-old children at the Neighbourhood Forum. He is clearly concerned about the matter. However, simply requesting more resources is not, in my view, responsible for a manager given the well known concern of members at the state of the Social Services budget. I expect more appropriate responses from people in management positions in Social Services. The obvious option for your management to consider in relation to this emerging problem in the area is to reduce the fieldwork staffing to release resources for a detached youth worker in the area. I await your response.”

“We couldn’t believe it,” recalls Mrs Davies. “We were grappling with this enormous problem and all she was concerned about was balancing her budget. It boggles the mind. It was as if we were talking about park benches, not children.”

Because this critical memo was not made available to Standard reporters at the time of the investiga-tion-only coming to light years later, in May 1995, Mrs Hodge was never made to explain how it was she knew about the allegations of abuse for over two years without fully pursuing them.

David Cofie, in a separate interview, says that the standard procedure would have been for the matter to be referred to the child protection committee for a full investigation, but that this did not happen. Mr Cofie says that Mrs Hodge resisted his requests that the matter be properly investigated on three separate occasions. “The first occasion was when I decided the only responsible thing was to alert the community to the fact that paedophiles were operating in the area,” he recalls. “I wrote a short, subtly-worded report that was to be dis-tributed to the Neighbourhood Forum, which is open to members of the public. Well, Margaret Hodge went apeshit. She started screaming and shouting at me and refused to discuss it. I later heard that she had rub-bished me to colleagues behind my back, saying that I was exaggerating the sexual abuse claims and trying to make a name for myself.

But my colleagues told her, ‘David would never do that. If anything, he’s one of the most overcautious managers we have.’ ” In May 1990, Mr Cofie and Mrs Davies were summoned to a meeting convened by Islington’s assistant director of social services, Lyn Cusack. “By now,” says Mrs Davies, “we knew that the picture was far worse than initially imagined. I had learned that children in our care were being taken to homes in the country on weekends. It was highly suspicious, and I would later discover that they were being used to make child pornography and that people who ran our homes were getting paid in hard cash. But we were criticised as ‘hysterical’ and told in no uncertain terms to stop interviewing children and to cease child protection conferences forthwith.”

Mrs Davies and Mr Cofie continued to investigate regardless. They wrote and submitted 15 detailed reports but maintain their superiors still did not believe them. When the paedophile Roy Caterer, whose name Mrs Davies passed to the police, went to prison, Mr Cofie said to Mrs Davies: “Now they’ve got to believe us.” But Mrs Hodge and Lyn Cusack and their acolytes – inexplicably – still weren’t interested. The crunch for Mrs Davies came when she was ordered to place a “looked-after” seven-year-old boy in a home that was run by someone she had raised concerns about and considered unsafe. Her position had become untenable.

At the same time, she had started having a recurring nightmare. In the dream, Mrs Davies would be drinking a lovely glass of cold white wine that would suddenly turn into jagged pieces of glass that cut her throat to bloody ribbons. A friend told her: “It’s obvious, Liz, it’s all too much for you to swallow.”

In February 1992, Mrs Davies resigned in despair and took her information to Mike Hames, then head of Scotland Yard’s Obscene Publications Unit. He commenced an investigation, subsequently exposed in the Standard by Eileen Fairweather and Stewart Payne. More than 50 reports were published in the paper – which Mrs Hodge scornfully condemned – leading eventually to five independent inquiries.

It was another two-and-a-half years before the damning White report would be published – singling out and naming 22 people who worked for Islington and whose names were never published. Mrs Hodge went on the record to say that she was led astray, that her only fault was in believing her senior officers like Lyn Cu-sack. Those on the inside – like Mrs Davies – have always believed this was a fudge.

The critical April 1990 memo, which we reprint above, shows that Mrs Hodge’s claim is, at the very least, an oversimplification. It shows that when Mrs Hodge was directly presented with details of the sexual abuse allegations uncovered by Mr Cofie and Mrs Davies, she was apparently more concerned with allocating re-sources than addressing the substance of the allegations.

By the time the White report was published, Mrs Hodge had moved on. She would take up a top job in the City, then become MP for Barking, and later Minister for Higher Education. And now she is Minister for Chil-dren. David Cofie, on the other hand, stayed on at Islington until he retired in 1998.

So did Mrs Hodge ever thank Mr Cofie for the role he played in bringing to light this appalling scandal?

” Hodge never thanked me,” Mr Cofie says. “Nor did she apologise. Even though she had wrecked my ca-reer, frozen me out, made me persona non grata.

She was never a big enough person to say to me, ‘I am sorry for how I treated you. I was wrong. Thank you for what you did to save those children.’ ” Mrs Davies is even more scathing.

“It beggars belief to think that Tony Blair has awarded Hodge the highest job in the land for protecting the welfare of our most vulnerable citizens.

Blair was her neighbour at the time. He must remember her appalling record.

What in heaven’s name was he thinking?”

How scandal unfolded

1982: Margaret Hodge becomes leader of Islington council

February 1990: Liz Davies and David Cofie, senior Islington social workers, uncover evidence of sexual abuse of children, and report it to a Neighbourhood Forum which council leader Margaret Hodge attends as ward councillor.

April 1990: Hodge memos Cofie’s boss, John Rea Price, the director of social services: “David Cofie raised the issue of sexual abuse among eight-to 16-year-old children. He is clearly concerned. However, simply requesting more resources is not responsible for a manager given the concern of members at the state of the social services budget. I expect more appropriate responses from people in management positions in social services”.

May 1990: At a key meeting chaired by Lyn Cusack, assistant director of social services, Cofie and Davies are told to cease interviewing children and to stop convening child protection conferences

1991: Roy Caterer, who worked at a school used by Islington council for its children in care, is arrested for sexually abusing seven boys and two girls, and is jailed for seven-and-a-half years. Cofie and Davies ask social services for resources to help the victims, but receive no reply

February 1992: Davies resigns and takes her information to Scotland Yard

6 October 1992: A Standard investigation reveals that a 15-year-old girl worked as a prostitute from a coun-cil home; a 16-year-old was made pregnant at a teenage unit by a man suspected of involvement in a child sex ring; a girl was knifed by a pimp at an Islington home; and a boy was abused for years by a volunteer instructor

14 October 1992: Hodge says of the Standard’s investigation: “The way they chose to report this was gutter journalism … The story misled the public on the quality of childcare services in the borough”

23 October 1992: Hodge steps down as council leader to take up a post as a senior consultant with ac-countancy firm Price Waterhouse

3 March 1993: The Press Complaints Commission rejects all Islington’s complaints against the Standard

11 February 1994: Hodge admits to the Standard: “You were right that there was abuse in the children’s homes,” and blames her initial response on “misleading” information from senior officers and colleagues

23 May 1995: Report by Ian White, Oxfordshire director of social services, backs the Standard and says care-home workers were able to corrupt children in part because Islington’s ideological policies prevented complaints being investigated. Hodge responds: “I have had no involvement with Islington council for three years. It would be inappropriate for me to comment”

26 May 1995: Hodge tells Radio 4: “Of course I accept responsibility. I was leader of the council at the time”

13 June 2003: Hodge becomes Minister for Children

27 June 2003: Hodge tells Women’s Hour on BBC Radio 4: “I don’t think that any of us recognised the danger of child abuse in children’s homes to the extent that we’re aware of it now. I’ve learned from my fail-ure to understand at that time”

Leon, Maggie, Elm Guest House, and the CGHE

In January, Exaro News and the Sunday People revealed that the Conservative Group for Homosexual Equality (CGHE) “strongly recommended” that its members visit the Elm Guest House, which was being used as a front for a paedophile ring that sexually abused children as young as 10 who had been procured from children’s homes run by Richmond Council. Full article

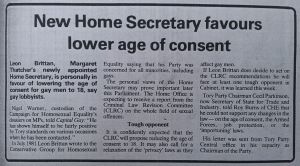

In 1983, Margaret Thatcher’s Home Secretary, Leon Brittan, wrote to the CGHE and as well as saying he supported the wholly reasonable aim of reducing the age of homosexual consent to 18, he told them that the Conservative Party supported “all minorities”. He didn’t specify whether this support included the paedophile minority.

The Paedophile Information Exchange (PIE), who campaigned for the age of consent to be reduced to 4 years old, had successfully infiltrated the gay liberation movement and positioned themselves as an oppressed minority group. They had also persuaded politicians to support their cause, and they claimed that two MPs were on their mailing list.

The Paedophile Information Exchange (PIE), who campaigned for the age of consent to be reduced to 4 years old, had successfully infiltrated the gay liberation movement and positioned themselves as an oppressed minority group. They had also persuaded politicians to support their cause, and they claimed that two MPs were on their mailing list.

Although it may seem far-fetched that any government would support a paedophile organisation, you only have to look at the Thatcher government’s record on child abuse to realise that the rights of paedophiles were given more importance than the rights of children. They refused to ban the Paedophile Information Exchange despite a petition which attracted over a million signatures from members of the public. Read more

The Conservative Group for Homosexual Equality were keen supporters of Thatcher, as we can see from these Capital Gay articles from April/May 1982, although she was less keen to show her support for them. Was this becase she was aware of their connections to the Elm Guest House and wanted to distance herself from them?

Some Labour politicians also supported paedophiles. The National Council for Civil Liberties (NCCL), now known as Liberty, whose officials included Harriet Harman, Patricia Hewitt, Jack Dromey, and Henry Hodge, were affiliated to PIE. In 1978 the NCCL passed a resolution which stated that images of child abuse should only be considered indecent if it could be proved that the children involved had suffered harm. Read more

Some Labour politicians also supported paedophiles. The National Council for Civil Liberties (NCCL), now known as Liberty, whose officials included Harriet Harman, Patricia Hewitt, Jack Dromey, and Henry Hodge, were affiliated to PIE. In 1978 the NCCL passed a resolution which stated that images of child abuse should only be considered indecent if it could be proved that the children involved had suffered harm. Read more

Former Liberal leader David Steel publicly attacked Tory MP Geoffrey Dickens for naming the senior diplomat Sir Peter Hayman as a paedophile. Liberal MP Sir Cyril Smith attended the Elm Guest House, and was also linked to child murderer Sidney Cooke, and leading PIE member Peter Righton, whose paedophile network preyed on children in schools and children’s homes across the UK.

There were also powerful Establishment figures outside the main political parties who were involved in covering up paedophile networks. The Attorney General, Sir Michael Havers, threatened Fleet Street over their coverage of the Elm Guest House paedophile network, and effectively stopped them from reporting on it after August 1982. Havers, along with the Director of Public Prosecutions, Sir Thomas Hetherington, protected paedophile diplomat Sir Peter Hayman, and Hetherington allowed the leader of the Paedophile Information Exchange to flee the country and escape a jail sentence.